Background

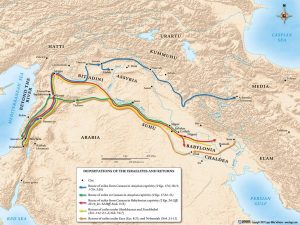

The book is named after Ezra, the faithful scribe who was prominent in the second major return of exiles to Judah in the year 458 BC (about eighty years after the first return of exiles under Zerubbabel in 536 BC). The personal name may well be an Aramaic form of the Hebrew word for “help.”

The book of Ezra was combined with the book of Nehemiah in the earliest Hebrew manuscripts as well as in the Septuagint. This was done in the same way as the double books (Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles) and the twelve minor prophets. The notations in the Masoretic text treat the two books as a unit in counting the verses and marking the middle one (at Nehemiah 3:32). In the first century AD Josephus referred to Ezra but not to Nehemiah, leading most to conclude that the latter was included in the reference to the former. The Talmud also speaks of Ezra writing “his book” (Ezra-Nehemiah), but additionally says that Nehemiah “finished it.”

However, it is most likely that these two books were not written as one or even by one author. Repetition with Ezra 2 and Nehemiah 7:6-70 points to these being two separates compositions. Other internal evidence, namely Nehemiah 1:1 plus the many first person references like Ezra 7:28, 8:1, Nehemiah 1:2ff., etc., also points to these being seprate compositions by separate authors. Furthermore, the Peshitta as well as the Vulgate separate the books. Why they were often treated as one book we really do not know, but possible explanations are that Nehemiah is a continuation of Ezra’s history and that uniting them made the total number of canonical books agree with the number of letters in the Hebrew alphabet. Another possibility is that the same person edited them or put them into their final forms.

Authorship

Any discussion of authorship for Ezra or for Nehemiah must include the observation that these books display many characteristics that are also common to 1 and 2 Chronicles. The concluding sentences of 2 Chronicles and the opening ones of Ezra are virtually identical. All of these books display a fondness of lists and for certain repeated phrases, for example “house of God” and “heads of families.” They focus largely on temple personnel like the gatekeepers, temple servants, and singers as well as on the family lines and functions of the Levitical priests. For these reasons some have suggested that Ezra wrote the Chronicles while others proposed that an unknown Chronicler wrote Chronicles, Ezra, and Nehemiah. We cannot be certain, but it is more likely that Ezra wrote Chronicles and the book that now goes by his name. This also agrees with Jewish tradition.

Purpose for Writing

An obvious theme of the book, one that also applies well to Nehemiah and Esther, is the powerful work of God to preserve his remnant for the sake of his promise of a Savior. “In these three books we see how the Lord ruled over the kings of the earth with quiet power which the kings hardly noticed. Without realizing it four kings of Persia, the greatest empire in the world, became the servants of God’s servants.”1Brug, John F. Ezra, Nehemiah, Esther. The People’s Bible. Milwaukee, WI: Northwestern Pub. House, 1985. 1. Phrased another way, we might say that Ezra shows how the Lord moved his unworthy people to embrace and respond to his gracious promises. Through Ezra as well as through Haggai, Zechariah, and Nehemiah, the Lord overcame the ingratitude, indifference, and backsliding of the people who had been brought back to Judah. In restoring Jerusalem physically and spiritually, the Lord affirmed his promises to renew the remnant. Ezra 10:2 may serve as a good theme for the whole book: “In spite of this (the unfaithfulness of the people), there is still hope for Israel.”

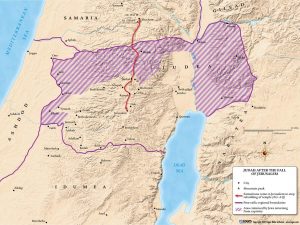

Another purpose would be the fact that we receive significant historical information in the postexilic, or Persian, period. Generally speaking, postexilic history from about 538 BC to sometime after 433 BC, a span of over one hundred years, is provided in the overlapping accounts of Ezra and Nehemiah.

Date

Historically, Ezra and Nehemiah are also close companions. The NIV Study Bible shows this while sharing this information: “According to the traditional view, Ezra arrived in Jerusalem in the seventh year (Ezra 7:8) of Artaxerxes I (458 BC), followed by Nehemiah, who arrived in the king’s 20th year (445 BC; Neh 2:1). Some have proposed a reverse order in which Nehemiah arrived in 445 BC, while Ezra arrived in the seventh year of Artaxerxes II (398 BC). By amending ‘seventh’ (Ezra 7:8) to either ‘27th’ or ‘37th,’ others place Ezra after Nehemiah but maintain they were contemporaries.”2Zondervan Publishing. Zondervan NIV Study Bible: New International Version. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2002.

We hold the traditional view of chronology since it presents fewer problems and reflects a straightforward understanding of the text. Placing Ezra’s ministry in the reign of Artaxerxes I (464-424 BC) also uses evidence from the Elephantine papyri. We also note that both Ezra and Nehemiah are together in Nehemiah 8:9 and Nehemiah 12:26, 36, and we usually date the writing of the books as approximately 440 BC for Ezra and 430 BC for Nehemiah.

See also the Chronology of Latter Prophets and Intertestamental Period.

Christ Connection

With the return from exile, God kept his promise to his people. The promise of the return is rooted in his promise not just to Abraham (Gen 12:1-3) but also to Adam and Eve (Gen 3:15). By settling his people back in the land of Israel, God was ready to make the final preparations in world history for the coming of the Savior roughly 500 years later.

Notable Passages

- Ezra 1:2-4

- Ezra 2:1

- Ezra 3:10-13

- Ezra 6:13-15

- Ezra 6:22

Outline

The most obvious way of dividing the book of Ezra is to do so on the basis of the returns from exile recorded in the book. Chapters 1-6 deal with the first exiles to return to Judah (538 BC) while chapters 7-10 focus on the activities of those who participated in the second return with Ezra in 458 BC. The first portion deals primarily with the rebuilding of the Jerusalem temple while the second part concentrates more directly on the reforming of people’s spiritual lives.

- The First Return to Judah with Zerubbabel (Ezr 1-6)

- The Second Return to Judah with Ezra (Ezr 7-10)

Another division could be as follows:

- First Emigration (Ezr 1-2)

- Restoration of the Temple (Ezr 3-6)

- Second Emigration (Ezr 7-8)

- Reformation after Intermarriage (Ezr 9-10)