Background

The title comes from the Hebrew word שָׁפַט that means “to judge”. The word itself not only means to “pass judgment,” as a judge does in court when deciding a case, but also to “execute judgment,” as a leader or ruler does when carrying out acts of deliverance or vindication in order that justice might prevail (see Ps 26:1; 43:1, etc.).

Thus the judges of Israel whose record is found in this book were special leaders, often military heroes, chosen by God to deliver his people from oppression. Sometimes after carrying out their act of deliverance they continued to rule over Israel many years (Othniel, Gideon, et al.). Sometimes they served only to drive away Israel’s enemies or relieve its oppression in a time of crisis (Shamgar, Samson). Some were great national heroes (Samson), while of others we have no record of great warlike deeds but simply the fact that they judged Israel a certain number of years (Tola, Jair). In one case, at least, a judge happened to have been a prophetess (Deborah).

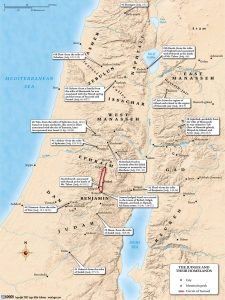

This was God’s way of ruling when Israel was a true theocracy (God was seen as their true king), not confined by any system of hereditary rule but with rulers chosen directly by God. In some cases two or more judges ruled contemporaneously – one east of Jordan while the other served west of Jordan – each acting in a restricted tribal area rather than over all of Israel. The further Israel gets from the more ordered time of Joshua, the more chaotic the situation becomes, with more judges ruling contemporaneously.1The introductory information on this page has been adapted from Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary’s Middler Isagogic Notes, which can be found here. Used with permission.

Authorship

As with the book of Joshua, we don’t know who wrote the book. Some say Samuel. Since the book covers a period of hundreds of years, there was a need for the writer to make use of sources. The internal makeup of the book testifies, however, to a single historian/author.

An oft-repeated refrain in the book: “In those days Israel had no king; everyone did as he saw fit” (Jdg 17:6; 18:1; 19:1; 21:25) indicates by implication that the book was written at a time when there was a king in Israel.

According to Judges 1:21 the book (or the source the historian used here) was written while Jebusites were still occupying Jerusalem. Since the Jebusites were not finally driven out of Jerusalem until David’s time (2 Sam 5:6ff), it is possible that the book was written before David’s conquest, no doubt some time in the early days of the monarchy.

Purpose for Writing

The book of Judges shows us how God preserved his covenant people in the promised land from the time of Joshua to the time of Samuel (approximately 350 years). The immorality of many of the leading characters shows that the real hero of the book and of the time period is the Lord.

Date

It is impossible to establish a consecutive chronology of the period of the Judges. To add together the years of the twelve judges consecutively results in a total of years between the Exodus and the building of the Temple about 70-100 years longer than the 480 years mentioned in 1 Kings 6:1 (Wilderness = 40 years; Conquest = 10 to 20 years; the twelve Judges = 410 years; Eli = 40 years; Samuel = 20 years; Saul = 20-40 years; David = 40 years; Solomon = 4 years.). Some of the judges, as mentioned previously, ruled simultaneously in different areas.

Martin Luther reckons the time “from the death of Moses to Samuel” as 350 years, stating that Acts 13:20 contains “a textual error” when it gives 450 years instead of 350. Luther’s understanding of this passage is based upon a faulty division of the text between v. 20 and v. 21 of Acts 13, leading to his misunderstanding of the era to which the 450 years refer. The NIV interprets the 450 years as a round number referring to the years in Egypt and the Wilderness. Merrill Unger places the time of Othniel, the first judge, at 1361 BC and the time of Saul at 1020 BC, indicating a span of 341 years during which judges ruled over Israel. This agrees closely with the estimate of Luther. Unger adds, however, that “these dates cannot be established with certainty.”2Unger, Merrill F. Archaeology and the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Pub. House, 1954. 179-187.

We recognize these time difficulties, aware that the Scriptures themselves never intended to give us a precise chronological table of judges in consecutive order, since the judges did not rule in chronological order (Jephthah, east of Jordan, overlapped Eli, Samson, Ibzan, Elon, Abdon, and Samuel west of Jordan – Jdg 10:7; 1 Sam 4:18). It is more important to appreciate the overall picture of this time element, a span covering several hundred years at least. This exceeds the historical time span of the United States of America, a fact which is often not fully realized or appreciated when considering the time span of the judges. And during this period of adjustment in a new land God took care of his own, in spite of their repeated perversity.

Content

The book of Judges does not give us a connected history of Israel as a whole, but rather presents a series of individual historical sketches in order to show the religious and moral degeneration, social defects, and national peril affecting the people of Israel on the one hand – as well as the repeated interventions of God for the purpose of preserving his people during the period of settling the promised land on the other.

The book names twelve individuals who are judges in the full sense of the word. Six of them are called major judges because a whole episode is devoted to them (Othniel, Ehud, Deborah, Gideon, Jephthah, and Samson). The other six are referred to as minor judges because little or nothing is said about them in the book (Shamgar, Tola, Jair, Ibzan, Elon, and Abdon). Eli and Samuel, who may overlap the last judges, may be classified as judges, but they are not treated until the book of Samuel. Barak, Deborah’s military leader, and Abimelech, Gideon’s son, are included in some listings, but in a strict sense are not to be considered as judges.

Christ Connection

Judges continues the historical account of God’s saving activity through the nation of Israel. Even though the Israelites turned their back on God time and again, he continued to preserve the promise of a Savior originally given to Adam and Eve (Gen 3:15) and continued through Abraham and his descendants (Gen 12:1-3).

The judges can also serve as a sort of picture of what God did by sending Christ. The judges were sent by God to save his people from their enemies. Similarly, God sent Jesus to save us from our enemies of sin, death, and Satan. Ultimately, when one reads the book of Judges, he or she cannot help but think of God’s graciousness in providing deliverance for his people even when they don’t deserve it.

Notable Passages

- Judges 2:16-19

- Judges 3:9,15

- Judges 5:31

- Judges 21:25

Outline

The book of Judges is organized around repeated cycles of idolatry, oppression, deliverance, and repentance.

INTRO – Possession of land not complete, apostasy growing (Ch 1-2)

1. Failure to purge the land.

2. Religious apostasy.

BODY – Israel’s sin and God’s grace (7 cycles) (12 judges) (Ch 3-16)

Cycle One: Othniel defeats Aram.

Cycle Two: Ehud defeats Moab / Shamgar

Cycle Three: Deborah (with Barak) defeats Canaan

Cycle Four: Gideon defeats Midian (Abimelech the anti-judge) / Tola, Jair

Cycle Five: Jephthah defeats Ammon / Ibzan, Elon, Abdon.

Cycle Six: Samson versus the Philistines

Appendix – Breakdown in family, tribe, nation, and clergy (Ch 17-21)

1. Micah and the Danites’ religious corruption

2. The Benjamites’ moral corruption

(Treating Abimelech / Tola / Jair as a cycle would produce seven cycles.)